Texas Revolution

| Texas Revolution | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The campaigns of the Texas Revolution | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| c. 2,000 | c. 6,500 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

- Northwest Ordinance

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise

- Tariff of 1828

- Nat Turner's Rebellion

- Nullification crisis

- End of slavery in British colonies

- Texas Revolution

- United States v. Crandall

- Gag rule

- Commonwealth v. Aves

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall

- American Slavery As It Is

- United States v. The Amistad

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- Texas annexation

- Mexican–American War

- Wilmot Proviso

- Nashville Convention

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin

- Recapture of Anthony Burns

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Ostend Manifesto

- Bleeding Kansas

- Caning of Charles Sumner

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The Impending Crisis of the South

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

- Virginia v. John Brown

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise

- Secession of Southern states

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment

- Battle of Fort Sumter

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) against the centralist government of Mexico in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas. Although the uprising was part of a larger one, the Mexican Federalist War,[citation needed] that included other provinces opposed to the regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican government believed the United States had instigated the Texas insurrection with the goal of annexation. The Mexican Congress passed the Tornel Decree, declaring that any foreigners fighting against Mexican troops "will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag". Only the province of Texas succeeded in breaking with Mexico, establishing the Republic of Texas. It was eventually annexed by the United States.

The revolution began in October 1835, after a decade of political and cultural clashes between the Mexican government and the increasingly large population of Anglo-American settlers in Texas. The Mexican government had become increasingly centralized and the rights of its citizens had become increasingly curtailed, particularly regarding immigration from the United States. Mexico had officially abolished slavery in Texas in 1829, and the desire of Anglo Texans to maintain the institution of chattel slavery in Texas was also a major cause of secession.[1][2][3][4][5] Colonists and Tejanos disagreed on whether the ultimate goal was independence or a return to the Mexican Constitution of 1824. While delegates at the Consultation (provisional government) debated the war's motives, Texians and a flood of volunteers from the United States defeated the small garrisons of Mexican soldiers by mid-December 1835. The Consultation declined to declare independence and installed an interim government, whose infighting led to political paralysis and a dearth of effective governance in Texas. An ill-conceived proposal to invade Matamoros siphoned much-needed volunteers and provisions from the fledgling Texian Army. In March 1836, a second political convention declared independence and appointed leadership for the new Republic of Texas.

Determined to avenge Mexico's honor, Santa Anna vowed to personally retake Texas. His Army of Operations entered Texas in mid-February 1836 and found the Texians completely unprepared. Mexican General José de Urrea led a contingent of troops on the Goliad Campaign up the Texas coast, defeating all Texian troops in his path and executing most of those who surrendered. Santa Anna led a larger force to San Antonio de Béxar (or Béxar), where his troops defeated the Texian garrison in the Battle of the Alamo, killing almost all of the defenders.

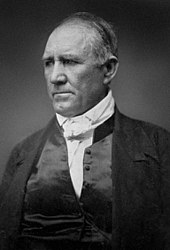

A newly created Texian army under the command of Sam Houston was constantly on the move, while terrified civilians fled with the army, in a melee known as the Runaway Scrape. On March 31, Houston paused his men at Groce's Landing on the Brazos River, and for the next two weeks, the Texians received rigorous military training. Becoming complacent and underestimating the strength of his foes, Santa Anna further subdivided his troops. On April 21, Houston's army staged a surprise assault on Santa Anna and his vanguard force at the Battle of San Jacinto. The Mexican troops were quickly routed, and vengeful Texians executed many who tried to surrender. Santa Anna was taken hostage; in exchange for his life, he ordered the Mexican army to retreat south of the Rio Grande. Mexico refused to recognize the Republic of Texas, and intermittent conflicts between the two countries continued into the 1840s. The annexation of Texas as the 28th state of the United States, in 1845, led directly to the Mexican–American War.

Background

[edit]After a failed attempt by France to colonize Texas in the late 17th century, Spain developed a plan to settle the region.[6] On its southern edge, along the Medina and Nueces Rivers, Spanish Texas was bordered by the province of Coahuila.[7] On the east, Texas bordered Louisiana.[8] Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the United States also claimed the land west of the Sabine River, all the way to the Rio Grande.[9] From 1812 to 1813 anti-Spanish republicans and U.S. filibusters rebelled against the Spanish Empire in what is known today as the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition during the Mexican War of Independence. They won battles in the beginning and captured many Texas cities from the Spanish that led to a declaration of independence of the state of Texas as part of the Mexican Republic on April 17, 1813. The new Texas government and army met their doom in the Battle of Medina in August 1813, 20 miles south of San Antonio, where 1,300 of the 1,400 rebel army were killed in battle or executed shortly afterwards by royalist soldiers. It was the deadliest single battle in Texas history. 300 republican government officials in San Antonio were captured and executed by the Spanish royalists shortly after the battle. Antonio López de Santa Anna, future President of Mexico, fought in this battle as a royalist and followed his superiors' orders to take no prisoners. Another interesting note is two founding fathers of the Republic of Texas and future signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence in 1836, José Antonio Navarro and José Francisco Ruiz, took part in the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition.[10] Although the United States officially renounced that claim as part of the Transcontinental Treaty with Spain in 1819,[Note 1] many Americans continued to believe that Texas should belong to their nation,[11] and over the next decade the United States made several offers to purchase the region.[12]

Following the Mexican War of Independence, Texas became part of Mexico. Under the Constitution of 1824, which defined the country as a federal republic, the provinces of Texas and Coahuila were combined to become the state Coahuila y Tejas.[Note 2][13][14] Texas was granted only a single seat in the state legislature, which met in Saltillo, hundreds of miles away.[15][16] After months of grumbling by Tejanos (Mexican-born residents of Texas) outraged at the loss of their political autonomy, state officials agreed to make Texas a department of the new state, with a de facto capital in San Antonio de Béxar.[15]

Texas was very sparsely settled, with fewer than 3,500 non-Native residents, and only about 200 soldiers,[17][18] which made it extremely vulnerable to attacks by native tribes and American filibusters.[19] In the hopes that an influx of settlers could control the Indigenous resistance, the bankrupt Mexican government liberalized immigration policies for the region. Finally able to settle legally in Texas, Anglos from the United States soon vastly outnumbered the Tejanos.[Note 3][20][21] Most of the immigrants came from the Southern United States. Many were slave owners, and most brought with them significant prejudices against other races, attitudes often applied to the Tejanos[citation needed]. Mexico's official religion was Roman Catholicism, yet the majority of the immigrants were Protestants who distrusted Catholics.[22]

Mexican authorities became increasingly concerned about the stability of the region.[12] The colonies teetered at the brink of revolt in 1829, after Mexico abolished slavery.[23] In response, President Anastasio Bustamante implemented the Laws of April 6, 1830, which, among other things, prohibited further immigration to Texas from the United States, increased taxes, and reiterated the ban on slavery.[24] Settlers simply circumvented or ignored the laws. By 1834, an estimated 30,000 Anglos lived in Coahuila y Tejas,[25] compared to only 7,800 Mexican-born residents.[26] By the end of 1835, almost 5,000 enslaved Africans and African Americans lived in Texas, making up 13 percent of the non-Indian population.[27]

In 1832, Antonio López de Santa Anna led a revolt to overthrow Bustamante.[28][29] Texians, or English-speaking settlers, used the rebellion as an excuse to take up arms[according to whom?][citation needed]. By mid-August, all Mexican troops had been expelled from east Texas.[30] Buoyed by their success, Texians held two political conventions to persuade Mexican authorities to weaken the Laws of April 6, 1830.[31] Bustamante was replaced by the liberal federalist Valentin Gomez Farias, who would attempt to reach a compromise with the Texans. In November 1833, the Mexican government attempted to address some of their concerns, repealing some sections of the law and granting the colonists further concessions,[32] including increased representation in the state legislature.[33] Stephen F. Austin, who had brought the first American settlers to Texas, wrote to a friend that "Every evil complained of has been remedied."[34] Mexican authorities were quietly watchful, concerned that the colonists were maneuvering towards secession.[35][36]

Santa Anna overthrew Gomez Farias in April 1834, and soon revealed himself to be a centralist, inaugurating the Centralist Republic of Mexico. In 1835, the 1824 Constitution was overturned; state legislatures were dismissed, militias disbanded.[37][38] Federalists throughout Mexico were appalled. Citizens in the states of Oaxaca and Zacatecas took up arms.[37] After Santa Anna's troops subdued the rebellion in Zacatecas in May, he gave his troops two days to pillage the city; over 2,000 noncombatants were killed.[39] The governor of Coahuila y Tejas, Agustín Viesca, refused to dissolve the legislature, instead ordering that the session reconvene in Béxar, further from the influence of the Mexican army.[40] Although prominent Tejano Juan Seguín raised a militia company to assist the governor, the Béxar ayuntamiento (city council) ordered him not to interfere,[41] and Viesca was arrested before he reached Texas.[42]

Public opinion in Texas was divided.[43] Editorials in the United States began advocating complete independence for Texas.[44] After several men staged a minor revolt against customs duties in Anahuac in June,[45] local leaders began calling for a public meeting to determine whether a majority of settlers favored independence, a return to federalism, or the status quo. Although some leaders worried that Mexican officials would see this type of gathering as a step towards revolution, by the end of August most communities had agreed to send delegates to the Consultation, scheduled for October 15.[46]

As early as April 1835, military commanders in Texas began requesting reinforcements, fearing the citizens would revolt.[47] Mexico was ill-prepared for a large civil war,[48] but continued unrest in Texas posed a significant danger to the power of Santa Anna and of Mexico. If the people of Coahuila also took up arms, Mexico faced losing a large portion of its territory. Without the northeastern province to act as a buffer, it was likely that United States influence would spread, and the Mexican territories of Nuevo Mexico and Alta California would be at risk of future American encroachment. Santa Anna had no wish to tangle with the United States, and he knew that the unrest needed to be subdued before the United States could be convinced to become involved.[49] In early September, Santa Anna ordered his brother-in-law, General Martín Perfecto de Cos, to lead 500 soldiers to Texas to quell any potential rebellion. Cos and his men landed at the port of Copano on September 20.[50] Austin called on all municipalities to raise militias to defend themselves.[51]

Texian offensive: October–December 1835

[edit]Gonzales

[edit]

In the early 1830s, the army loaned the citizens of Gonzales a small cannon for protection against Indian raids.[52] After a Mexican soldier bludgeoned a Gonzales resident on September 10, 1835, tensions rose even further, and Mexican authorities felt it unwise to leave the settlers with a weapon.[53] Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea, commander of all Mexican military forces in Texas, sent a small detachment of troops to retrieve the cannon.[39] After settlers escorted the group from town without the cannon, Ugartechea sent 100 dragoons with Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda to demand compliance, with orders to avoid force if possible.[39][54]

Many of the settlers believed Mexican authorities were manufacturing an excuse to attack the town and eliminate the militia.[55] Texians stalled Castañeda's attempts to negotiate the cannon's return for several days as they waited for reinforcements from other colonies.[56] In the early hours of October 2, approximately 140 Texian volunteers attacked Castañeda's force. After a brief skirmish, Castañeda requested a meeting with Texian leader John Henry Moore. Castañeda revealed that he shared their federalist leanings, but that he was honor-bound to follow orders. As Moore returned to camp, the Texians raised a homemade white banner with an image of the cannon painted in black in the center, over the words "Come and Take It". Realizing that he was outnumbered and outgunned, Castañeda led his troops back to Béxar.[57] In this first battle of the revolution, two Mexican soldiers were killed, and one Texian was injured when he fell off his horse.[58] Although the event was, as characterized by historian William C. Davis, "an inconsequential skirmish in which one side did not try to fight", Texians soon declared it a victory over Mexican troops.[58] News of the skirmish spread throughout the United States, encouraging many adventurers to come to Texas to join the fight.[59]

Volunteers continued to arrive in Gonzales. On October 11, the troops unanimously elected Austin, who had no official military experience, the leader of the group he had dubbed the Army of the People.[60][61] From the beginning, the volunteer army proved to have little discipline. Austin's first official order was to remind his men that they were expected to obey their commanding officers.[60] Buoyed by their victory, the Texians were determined to drive the Mexican army out of Texas, and they began preparing to march to Béxar.[53]

Gulf Coast campaign

[edit]After learning that Texian troops had attacked Castañeda at Gonzales, Cos made haste for Béxar. Unaware of his departure, on October 6, Texians in Matagorda marched on Presidio La Bahía in Goliad to kidnap him and steal the $50,000 that was rumored to accompany him.[62] On October 10, approximately 125 volunteers, including 30 Tejanos, stormed the presidio. The Mexican garrison surrendered after a thirty-minute battle.[63] One or two Texians were wounded and three Mexican soldiers were killed with seven more wounded.[64]

The Texians established themselves in the presidio, under the command of Captain Philip Dimmitt, who immediately sent all the local Tejano volunteers to join Austin on the march to Béxar.[65] At the end of the month, Dimmitt sent a group of men under Ira Westover to engage the Mexican garrison at Fort Lipantitlán, near San Patricio.[66] Late on November 3, the Texians took the undermanned fort without firing a shot.[67] After dismantling the fort, they prepared to return to Goliad. The remainder of the Mexican garrison, which had been out on patrol, approached.[68] The Mexican troops were accompanied by 15–20 loyal centralists from San Patricio, including all members of the ayuntamiento.[69] After a thirty-minute skirmish, the Mexican soldiers and Texian centralists retreated.[70] With their departure, the Texian army controlled the Gulf Coast, forcing Mexican commanders to send all communication with the Mexican interior overland. The slower land journey left Cos unable to quickly request or receive reinforcements or supplies.[68][71]

On their return to Goliad, Westover's group encountered Governor Viesca. After being freed by sympathetic soldiers, Viesca had immediately traveled to Texas to recreate the state government. Dimmitt welcomed Viesca but refused to recognize his authority as governor. This caused an uproar in the garrison, as many supported the governor. Dimmitt declared martial law and soon alienated most of the local residents.[72] Over the next few months, the area between Goliad and Refugio descended into civil war. Goliad native Carlos de la Garza led a guerrilla warfare campaign against the Texian troops.[73] According to historian Paul Lack, the Texian "antiguerilla tactics did too little to crush out opposition but quite enough to sway the uncommitted toward the centralists."[74]

Siege of Béxar

[edit]While Dimmitt supervised the Texian forces along the Gulf Coast, Austin led his men towards Béxar to engage Cos and his troops.[75] Confident that they would quickly rout the Mexican troops, many Consultation delegates chose to join the military. Unable to reach a quorum, the Consultation was postponed until November 1.[76] On October 16, the Texians paused 25 miles (40 km) from Béxar. Austin sent a messenger to Cos giving the requirements the Texians would need to lay down their arms and "avoid the sad consequences of the Civil War which unfortunately threatens Texas".[77] Cos replied that Mexico would not "yield to the dictates of foreigners".[78]

The approximately 650 Mexican troops quickly built barricades throughout the town.[53][79] Within days the Texian army, about 450 strong, initiated a siege of Béxar,[79] and gradually moved their camp nearer Béxar.[80] On October 27, an advance party led by James Bowie and James Fannin chose Mission Concepción as the next campsite and sent for the rest of the Texian army.[81] On learning that the Texians were temporarily divided, Ugartechea led troops to engage Bowie and Fannin's men.[82] The Mexican cavalry was unable to fight effectively in the wooded, riverbottom terrain, and the weapons of the Mexican infantry had a much shorter range than those of the Texians.[83] After three Mexican infantry attacks were repulsed, Ugartechea called for a retreat.[84] One Texian soldier had died, and between 14 and 76 Mexican soldiers were killed.[Note 4] Although Texas Tech University professor emeritus Alwyn Barr noted that the battle of Concepción "should have taught ... lessons on Mexican courage and the value of a good defensive position",[85] Texas history expert Stephen Hardin believes that "the relative ease of the victory at Concepción instilled in the Texians a reliance on their long rifles and a contempt for their enemies".[86]

As the weather turned colder and rations grew smaller, groups of Texians began to leave, most without permission.[87] Morale was boosted on November 18, when the first group of volunteers from the United States, the New Orleans Greys, joined the Texian army.[88][89] Unlike the majority of the Texian volunteers, the Greys looked like soldiers, with uniforms, well-maintained rifles, adequate ammunition, and some semblance of discipline.[89]

After Austin resigned his command to become a commissioner to the United States, soldiers elected Edward Burleson as their new commander.[90] On November 26, Burleson received word that a Mexican pack train of mules and horses, accompanied by 50–100 Mexican soldiers, was within 5 miles (8.0 km) of Béxar.[91][92] After a near mutiny, Burleson sent Bowie and William H. Jack with cavalry and infantry to intercept the supplies.[92][93] In the subsequent skirmish, the Mexican forces were forced to retreat to Béxar, leaving their cargo behind. To the disappointment of the Texians, the saddlebags contained only fodder for the horses; for this reason the battle was later known as the Grass Fight.[94] Although the victory briefly uplifted the Texian troops, morale continued to fall as the weather turned colder and the men grew bored.[95] After several proposals to take Béxar by force were voted down by the Texian troops,[96] on December 4 Burleson proposed that the army lift the siege and retreat to Goliad until spring. In a last effort to avoid a retreat, Colonel Ben Milam personally recruited units to participate in an attack. The following morning, Milam and Colonel Frank W. Johnson led several hundred Texians into the city. Over the next four days, Texians fought their way from house to house towards the fortified plazas near the center of town.[Note 5][97]

Cos received 650 reinforcements on December 8,[98] but to his dismay most of them were raw recruits, including many convicts still in chains.[99] Instead of being helpful, the reinforcements were mainly a drain on the dwindling food supplies.[98] Seeing few other options, on December 9, Cos and the bulk of his men withdrew into the Alamo Mission on the outskirts of Béxar. Cos presented a plan for a counterattack; cavalry officers believed that they would be surrounded by Texians and refused their orders.[100] Possibly 175 soldiers from four of the cavalry companies left the mission and rode south; Mexican officers later claimed the men misunderstood their orders and were not deserting.[99] The following morning, Cos surrendered.[101] Under the terms of the surrender, Cos and his men would leave Texas and no longer fight against supporters of the Constitution of 1824.[102] With his departure, there was no longer an organized garrison of Mexican troops in Texas,[103] and many of the Texians believed that the war was over.[104] Burleson resigned his leadership of the army on December 15 and returned to his home. Many of the men did likewise, and Johnson assumed command of the 400 soldiers who remained.[102][105]

According to Barr the large number of American volunteers in Béxar "contributed to the Mexican view that Texian opposition stemmed from outside influences".[106] In reality, of the 1,300 men who volunteered to fight for the Texian army in October and November 1835, only 150–200 arrived from the United States after October 2. The rest were residents of Texas with an average immigration date of 1830.[Note 6] Volunteers came from every municipality, including those that were partially occupied by Mexican forces.[107] However, as residents returned to their homes following Cos's surrender, the Texian army composition changed dramatically. Of the volunteers serving from January through March 1836, 78 percent had arrived from the United States after October 2, 1835.[Note 7][108] Texian immigration prior to 1835 can also be understood in the context of the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Slave states sought to maintain chattel slavery while free states wanted to phase out the practice. Expansion and annexation of territory below the compromise parallel can be viewed as attempts by slave states to gain an advantage in Congress or to at least bypass the Thomas amendment.

Regrouping: November 1835 – February 1836

[edit]Texas Consultation and the Matamoros Expedition

[edit]The Consultation finally convened on November 3 in San Felipe with 58 of the 98 elected delegates.[109] After days of bitter debate, the delegates voted to create a provisional government based on the principles of the Constitution of 1824. Although they did not declare independence, the delegates insisted they would not rejoin Mexico until federalism had been reinstated.[110] The new government would consist of a governor and a General Council, with one representative from each municipality. Under the assumption that these two branches would cooperate, there was no system of checks and balances.[111][112]

On November 13, delegates voted to create a regular army and named Sam Houston its commander-in-chief.[113] In an effort to attract volunteers from the United States, soldiers would be granted land bounties. This provision was significant, as all public land was owned by the state or the federal government, indicating that the delegates expected Texas to eventually declare independence.[114] Houston was given no authority over the volunteer army led by Austin, which predated the Consultation.[113] Houston was also appointed to the Select Committee on Indian Affairs. Three men, including Austin, were asked to go to the United States to gather money, volunteers, and supplies.[112] The delegates elected Henry Smith as governor.[115] On November 14, the Consultation adjourned, leaving Smith and the Council in charge.[116]

The new Texas government had no funds, so the military was granted the authority to impress supplies. This policy soon resulted in an almost universal hatred of the council, as food and supplies became scarce, especially in the areas around Goliad and Béxar, where Texian troops were stationed.[117] Few of the volunteers agreed to join Houston's regular army.[118] The Telegraph and Texas Register noted that "some are not willing, under the present government, to do any duty ... That our government is bad, all acknowledge, and no one will deny."[119]

Leaders in Texas continued to debate whether the army was fighting for independence or a return to federalism.[118] On December 22, Texian soldiers stationed at La Bahía issued the Goliad Declaration of Independence.[120] Unwilling to decide the matter themselves, the Council called for another election, for delegates to the Convention of 1836. The Council specifically noted that all free white males could vote, as well as Mexicans who did not support centralism.[121] Smith tried to veto the latter requirement, as he believed even Tejanos with federalist leanings should be denied suffrage.[122]

Leading federalists in Mexico, including former governor Viesca, Lorenzo de Zavala, and José Antonio Mexía, were advocating a plan to attack centralist troops in Matamoros.[123] Council members were taken with the idea of a Matamoros Expedition. They hoped it would inspire other federalist states to revolt and keep the bored Texian troops from deserting the army. Most importantly, it would move the war zone outside Texas.[124] The Council officially approved the plan on December 25, and on December 30 Johnson and his aide Dr. James Grant took the bulk of the army and almost all of the supplies to Goliad to prepare for the expedition.[105] Historian Stuart Reid posits that Grant was secretly in the employ of the British government, and that his plan to capture Matamoros, and thus tie Texas more tightly to Mexico, may have been an unofficial plan of his to advance the interests of his employers in the region.[125][Note 8]

Petty bickering between Smith and the Council members increased dramatically, and on January 9, 1836, Smith threatened to dismiss the Council unless they agreed to revoke their approval of the Matamoros Expedition.[126][127] Two days later the Council voted to impeach Smith and named James W. Robinson the Acting Governor.[128] It was unclear whether either side actually had the authority to dismiss the other.[129] By this point, Texas was essentially in anarchy.[130]

Under orders from Smith, Houston successfully dissuaded all but 70 men from continuing to follow Johnson.[131] With his own authority in question following Smith's impeachment, Houston washed his hands of the army and journeyed to Nacogdoches to negotiate a treaty with Cherokee leaders. Houston vowed that Texas would recognize Cherokee claims to land in East Texas as long as the Indians refrained from attacking settlements or assisting the Mexican army.[132] In his absence, Fannin, as the highest-ranking officer active in the regular army, led the men who did not want to go to Matamoros to Goliad.[133]

The council had neglected to provide specific instructions on how to structure the February vote for convention delegates, leaving it up to each municipality to determine how to balance the desires of the established residents against those of the volunteers newly arrived from the United States.[134] Chaos ensued; in Nacogdoches, the election judge turned back a company of 40 volunteers from Kentucky who had arrived that week. The soldiers drew their weapons; Colonel Sidney Sherman announced that he "had come to Texas to fight for it and had as soon commence in the town of Nacogdoches as elsewhere".[135] Eventually, the troops were allowed to vote.[135] With rumors that Santa Anna was preparing a large army to advance into Texas, rhetoric degenerated into framing the conflict as a race war between Anglos defending their property against, in the words of David G. Burnet, a "mongrel race of degenerate Spaniards and Indians more depraved than they".[136]

Mexican Army of Operations

[edit]

News of the armed uprising at Gonzales reached Santa Anna on October 23.[49] Aside from the ruling elite and members of the army, few in Mexico knew or cared about the revolt. Those with knowledge of the events blamed the Anglos for their unwillingness to conform to the laws and culture of their new country. Anglo immigrants had forced a war on Mexico, and Mexican honor insisted that the usurpers be defeated.[137] Santa Anna transferred his presidential duties to Miguel Barragán in order to personally lead troops to put an end to the Texian revolt. Santa Anna and his soldiers believed that the Texians would be quickly cowed.[138] The Mexican Secretary of War, José María Tornel, wrote: "The superiority of the Mexican soldier over the mountaineers of Kentucky and the hunters of Missouri is well known. Veterans seasoned by 20 years of wars can't be intimidated by the presence of an army ignorant of the art of war, incapable of discipline, and renowned for insubordination."[138]

At this time, there were only 2,500 soldiers in the Mexican interior. This was not enough to crush a rebellion and provide security – from attacks by both Indians and federalists – throughout the rest of the country.[139] According to author Will Fowler, Santa Anna financed the Texas expedition with three loans; one from the city of San Luis Potosí, and the other two loans from individuals Cayetano Rubio and Juan N. Errazo. Santa Anna had guaranteed at least a portion of the repayments with his own financial holdings.[140] He began to assemble a new army, which he dubbed the Army of Operations in Texas. A majority of the troops had been conscripted or were convicts who chose service in the military over jail.[141] The Mexican officers knew that the Brown Bess muskets they carried lacked the range of the Texian weapons, but Santa Anna was convinced that his superior planning would nonetheless result in an easy victory. Corruption was rampant, and supplies were not plentiful. Almost from the beginning, rations were short, and there were no medical supplies or doctors. Few troops were issued heavy coats or blankets for the winter.[142]

In late December, at Santa Anna's behest, the Mexican Congress passed the Tornel Decree, declaring that any foreigners fighting against Mexican troops "will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag."[143] In the early nineteenth century, captured pirates were executed immediately. The resolution thus gave the Mexican army permission to take no prisoners in the war against the Texians.[143] This information was not widely distributed, and it is unlikely that most of the American recruits serving in the Texian army were aware that there would be no prisoners-of-war.[144]

By December 1835, 6,019 soldiers had begun their march towards Texas.[145] Progress was slow. There were not enough mules to transport all of the supplies, and many of the teamsters, all civilians, quit when their pay was delayed. The large number of soldaderas – women and children who followed the army – reduced the already scarce supplies.[146] In Saltillo, Cos and his men from Béxar joined Santa Anna's forces.[147] Santa Anna regarded Cos's promise not to take up arms in Texas as meaningless because it had been given to rebels.[148]

From Saltillo, the army had three choices: advance along the coast on the Atascocita Road from Matamoros to Goliad, or march on Béxar from the south, along the Laredo road, or from the west, along the Camino Real.[149] Santa Anna ordered General José de Urrea to lead 550 troops to Goliad.[148][150] Although several of Santa Anna's officers argued that the entire army should advance along the coast, where supplies could be gained via sea,[145] Santa Anna instead focused on Béxar, the political center of Texas and the site of Cos's defeat.[145] His brother-in-law's surrender was seen as a blow to the honor of his family and to Mexico; Santa Anna was determined to restore both.[145] Santa Anna may also have thought Béxar would be easier to defeat, as his spies had informed him that most of the Texian army was along the coast, preparing for the Matamoros Expedition.[151] Santa Anna led the bulk of his men up the Camino Real to approach Béxar from the west, confounding the Texians, who had expected any advancing troops to approach from the south.[152] On February 17, they crossed the Nueces River, officially entering Texas.[151]

Temperatures reached record lows, and by February 13 an estimated 15–16 inches (38–41 cm) of snow had fallen. A large number of the new recruits were from the tropical climate of the Yucatán and had been unable to acclimate to the harsh winter conditions. Some of them died of hypothermia,[153] and others contracted dysentery. Soldiers who fell behind were sometimes killed by Comanche raiding parties.[154] Nevertheless, the army continued to march towards Béxar. As they progressed, settlers in their path in South Texas evacuated northward. The Mexican army ransacked and occasionally burned the vacant homes.[155] Santa Anna and his commanders received timely intelligence on Texian troop locations, strengths, and plans, from a network of Tejano spies organized by de la Garza.[156]

Santa Anna's offensive: February–March 1836

[edit]Alamo

[edit]

Fewer than 100 Texian soldiers remained at the Alamo Mission in Béxar, under the command of Colonel James C. Neill.[105] Unable to spare the number of men necessary to mount a successful defense of the sprawling facility,[157] in January Houston sent Bowie with 30 men to remove the artillery and destroy the complex.[158][Note 9] In a letter to Governor Smith, Bowie argued that "the salvation of Texas depends in great measure on keeping Béxar out of the hands of the enemy. It serves as the frontier picquet guard, and if it were in the possession of Santa Anna, there is no stronghold from which to repel him in his march towards the Sabine."[158][Note 10] The letter to Smith ended, "Colonel Neill and myself have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy."[158] Few reinforcements were authorized; cavalry officer William B. Travis arrived in Béxar with 30 men on February 3, and five days later a small group of volunteers arrived, including the famous frontiersman Davy Crockett.[159] On February 11, Neill left to recruit additional reinforcements and gather supplies.[160] In his absence, Travis and Bowie shared command.[148]

When scouts brought word on February 23 that the Mexican advance guard was in sight, the unprepared Texians gathered what food they could find in town and fell back to the Alamo.[150] By late afternoon, Béxar was occupied by about 1,500 Mexican troops, who quickly raised a blood-red flag signifying no quarter.[161] For the next 13 days, the Mexican army besieged the Alamo. Several small skirmishes gave the defenders much-needed optimism, but had little real impact.[162][163] Bowie fell ill on February 24, leaving Travis in sole command of the Texian forces.[164] The same day, Travis sent messengers with a letter To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World, begging for reinforcements and vowing "victory or death"; this letter was reprinted throughout the United States and much of Europe.[162] Texian and American volunteers began to gather in Gonzales, waiting for Fannin to arrive and lead them to reinforce the Alamo.[165] After days of indecision, on February 26 Fannin prepared to march his 300 troops to the Alamo; they turned back the next day.[166] Fewer than 100 Texian reinforcements reached the fort.[167]

Approximately 1,000 Mexican reinforcements arrived on March 3.[168] The following day, a local woman, likely Bowie's relative Juana Navarro Alsbury, was rebuffed by Santa Anna when she attempted to negotiate a surrender for the Alamo defenders.[169] This visit increased Santa Anna's impatience, and he scheduled an assault for early on March 6.[170] Many of his officers were against the plan; they preferred to wait until the artillery had further damaged the Alamo's walls and the defenders were forced to surrender.[171] Santa Anna was convinced that a decisive victory would improve morale and sound a strong message to those still agitating in the interior and elsewhere in Texas.[172]

In the early hours of March 6, the Mexican army attacked the fort.[173] Troops from Béxar were excused from the front lines, so that they would not be forced to fight their families and friends.[170] In the initial moments of the assault the Mexican troops were at a disadvantage. Although their column formation allowed only the front rows of soldiers to fire safely, inexperienced recruits in the back also discharged their weapons; many Mexican soldiers were unintentionally killed by their own comrades.[174] As Mexican soldiers swarmed over the walls, at least 80 Texians fled the Alamo and were cut down by Mexican cavalry.[175] Within an hour, almost all of the Texian defenders, estimated at 182–257 men, were killed.[Note 11] Between four and seven Texians, possibly including Crockett, surrendered. Although General Manuel Fernández Castrillón attempted to intercede on their behalf, Santa Anna insisted that the prisoners be executed immediately.[176]

Most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded.[177][178] This would represent about one-third of the Mexican soldiers involved in the final assault, which historian Timothy Todish remarks is "a tremendous casualty rate by any standards".[177] The battle was militarily insignificant but had an enormous political impact. Travis had succeeded in buying time for the Convention of 1836, scheduled for March 1, to meet. If Santa Anna had not paused in Béxar for two weeks, he would have reached San Felipe by March 2 and very likely would have captured the delegates or caused them to flee.[179]

The survivors, primarily women and children, were questioned by Santa Anna and then released.[177] Susanna Dickinson was sent with Travis's slave Joe to Gonzales, where she lived, to spread the news of the Texian defeat. Santa Anna assumed that knowledge of the disparity in troop numbers and the fate of the Texian soldiers at the Alamo would quell the resistance,[180] and that Texian soldiers would quickly leave the territory.[181]

Goliad Campaign

[edit]Urrea reached Matamoros on January 31. A committed federalist himself, he soon convinced other federalists in the area that the Texians' ultimate goal was secession and their attempt to spark a federalist revolt in Matamoros was just a method of diverting attention from themselves.[182] Mexican double agents continued to assure Johnson and Grant that they would be able to take Matamoros easily.[183] While Johnson waited in San Patricio with a small group of men, Grant and between 26 and 53 others roamed the area between the Nueces River and Matamoros.[184] Although they were ostensibly searching for more horses, it is likely Grant was also attempting to contact his sources in Matamoros to further coordinate an attack.[185]

Just after midnight on February 27, Urrea's men surprised Johnson's forces. Six Texians, including Johnson, escaped; the remainder were captured or killed.[186] After learning of Grant's whereabouts from local spies, Mexican dragoons ambushed the Texians at Agua Dulce Creek on March 2.[187] Twelve Texians were killed, including Grant, four were captured, and six escaped.[188] Although Urrea's orders were to execute those captured, he instead sent them to Matamoros as prisoners.[189]

On March 11, Fannin sent Captain Amon B. King to help evacuate settlers from the mission in Refugio. King and his men instead spent a day searching local ranches for centralist sympathizers. They returned to the mission on March 12 and were soon besieged by Urrea's advance guard and de la Garza's Victoriana Guardes.[190] That same day, Fannin received orders from Houston to destroy Presidio La Bahía (by then renamed Fort Defiance) and march to Victoria. Unwilling to leave any of his men behind, Fannin sent William Ward with 120 men to help King's company.[191][166] Ward's men drove off the troops besieging the church, but rather than return to Goliad, they delayed a day to conduct further raids on local ranches.[192]

Urrea arrived with almost 1,000 troops on March 14.[193] At the battle of Refugio, an engagement markedly similar to the battle of Concepción, the Texians repulsed several attacks and inflicted heavy casualties, relying on the greater accuracy and range of their rifles.[194] By the end of the day, the Texians were hungry, thirsty, tired, and almost out of ammunition.[195] Ward ordered a retreat, and under cover of darkness and rain the Texian soldiers slipped through Mexican lines, leaving several severely wounded men behind.[196] Over the next several days, Urrea's men, with the help of local centralist supporters, rounded up many of the Texians who had escaped. Most were executed, although Urrea pardoned a few after their wives begged for their lives, and Mexican Colonel Juan José Holzinger insisted that all of the non-Americans be spared.[196]

By the end of the day on March 16, the bulk of Urrea's forces began marching to Goliad to corner Fannin.[197] Still waiting for word from King and Ward, Fannin continued to delay his evacuation from Goliad.[198] As they prepared to leave on March 18, Urrea's advance guard arrived. For the rest of the day, the two cavalries skirmished aimlessly, succeeding only in exhausting the Texian oxen, which had remained hitched to their wagons with no food or water throughout the day.[199][200]

The Texians began their retreat on March 19. The pace was unhurried, and after travelling only 4 miles (6.4 km), the group stopped for an hour to rest and allow the oxen to graze.[198] Urrea's troops caught up to the Texians later that afternoon, while Fannin and his force of about 300 men were crossing a prairie.[201] Having learned from the fighting at Refugio, Urrea was determined that the Texians would not reach the cover of timber approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) ahead, along Coleto Creek.[202] As Mexican forces surrounded them, the Texians formed a tight hollow square for defense.[201] They repulsed three charges during this battle of Coleto, resulting in about nine Texians killed and 51 wounded, including Fannin. Urrea lost 50 men, with another 140 wounded. Texians had little food, no water, and declining supplies of ammunition, but voted to not try to break for the timber, as they would have had to leave the wounded behind.[203]

The following morning, March 20, Urrea paraded his men and his newly arrived artillery.[204] Seeing the hopelessness of their situation, the Texians with Fannin surrendered. Mexican records show that the Texians surrendered at discretion; Texian accounts claim that Urrea promised the Texians would be treated as prisoners-of-war and granted passage to the United States.[205] Two days later, a group of Urrea's men surrounded Ward and the last of his group less than 1 mile (1.6 km) from Victoria. Over Ward's vehement objections, his men voted to surrender, later recalling they were told they would be sent back to the United States.[206][207]

On Palm Sunday, March 27, Fannin, Ward, Westover, and their men were marched out of the presidio and shot. Mexican cavalry were stationed nearby to chase down any who tried to escape.[208] Approximately 342 Texians died,[209] and 27 either escaped or were spared by Mexican troops.[210] Several weeks after the Goliad massacre, the Mexican Congress granted an official reprieve to any Texas prisoners who had incurred capital punishment.[211]

Texas Convention of 1836

[edit]The Convention of 1836 in Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 1 attracted 45 delegates, representing 21 municipalities.[212] Within an hour of the convention's opening, George C. Childress submitted a proposed Texas Declaration of Independence, which passed overwhelmingly on March 2.[136][213] On March 6, hours after the Alamo had fallen, Travis's final dispatch arrived. His distress was evident; delegate Robert Potter immediately moved that the convention be adjourned and all delegates join the army.[214] Houston convinced the delegates to remain, and then left to take charge of the army. With the backing of the convention, Houston was now commander-in-chief of all regular, volunteer, and militia forces in Texas.[175]

Over the next ten days, delegates prepared a constitution for the Republic of Texas. Parts of the document were copied verbatim from the United States Constitution; other articles were paraphrased. The new nation's government was structured similarly to that of the United States, with a bicameral legislature, a chief executive, and a supreme court.[215] In a sharp departure from its model, the new constitution expressly permitted impressment of goods and forced housing for soldiers. It also explicitly legalized slavery and recognized the people's right to revolt against government authority.[216] After adopting the constitution on March 17, delegates elected interim officers to govern the country and then adjourned. David G. Burnet, who had not been a delegate, was elected president.[217] The following day, Burnet announced the government was leaving for Harrisburg.[218]

Retreat: March–May 1836

[edit]Texian retreat: The Runaway Scrape

[edit]On March 11, Santa Anna sent one column of troops to join Urrea, with instructions to move to Brazoria once Fannin's men had been neutralized. A second set of 700 troops under General Antonio Gaona would advance along the Camino Real to Mina, and then on to Nacogdoches. General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma would take an additional 700 men to San Felipe. The Mexican columns were thus moving northeast on roughly parallel paths, separated by 40–50 miles (64–80 km).[219]

The same day that Mexican troops departed Béxar, Houston arrived in Gonzales and informed the 374 volunteers (some without weapons) gathered there that Texas was now an independent republic.[220] Just after 11 p.m. on March 13, Susanna Dickinson and Joe brought news that the Alamo garrison had been defeated and the Mexican army was marching towards Texian settlements. A hastily convened council of war voted to evacuate the area and retreat. The evacuation commenced at midnight and happened so quickly that many Texian scouts were unaware the army had moved on. Everything that could not be carried was burned, and the army's only two cannon were thrown into the Guadalupe River.[221] When Ramírez y Sesma reached Gonzales the morning of March 14, he found the buildings still smoldering.[222]

Most citizens fled on foot, many carrying their small children. A cavalry company led by Seguín and Salvador Flores were assigned as rear guard to evacuate the more isolated ranches and protect the civilians from attacks by Mexican troops or Indians.[223] The further the army retreated, the more civilians joined the flight.[224] For both armies and the civilians, the pace was slow; torrential rains had flooded the rivers and turned the roads into mud pits.[225]

As news of the Alamo's fall spread, volunteer ranks swelled, reaching about 1,400 men on March 19.[225] Houston learned of Fannin's defeat on March 20 and realized his army was the last hope for an independent Texas. Concerned that his ill-trained and ill-disciplined force would only be good for one battle and aware that his men could easily be outflanked by Urrea's forces, Houston continued to avoid engagement, to the immense displeasure of his troops.[226] By March 28, the Texian army had retreated 120 miles (190 km) across the Navidad and Colorado Rivers.[227] Many troops deserted; those who remained grumbled that their commander was a coward.[226]

On March 31, Houston paused his men at Groce's Landing, roughly 15 miles (24 km) north of San Felipe.[Note 12] Two companies that refused to retreat further than San Felipe were assigned to guard the crossings on the Brazos River.[228] For the next two weeks, the Texians rested, recovered from illness, and, for the first time, began practicing military drills. While there, two cannons, known as the Twin Sisters, arrived from Cincinnati, Ohio.[229] Interim Secretary of War Thomas Rusk joined the camp, with orders from Burnet to replace Houston if he refused to fight. Houston quickly persuaded Rusk that his plans were sound.[229] Secretary of State Samuel P. Carson advised Houston to continue retreating all the way to the Sabine River, where more volunteers would likely flock from the United States and allow the army to counterattack.[Note 13][230] Unhappy with everyone involved, Burnet wrote to Houston: "The enemy are laughing you to scorn. You must fight them. You must retreat no further. The country expects you to fight. The salvation of the country depends on your doing so."[229] Complaints within the camp became so strong that Houston posted notices that anyone attempting to usurp his position would be court-martialed and shot.[231]

Santa Anna and a smaller force had remained in Béxar. After receiving word that the acting president, Miguel Barragán, had died, Santa Anna seriously considered returning to Mexico City to solidify his position. Fear that Urrea's victories would position him as a political rival convinced Santa Anna to remain in Texas to personally oversee the final phase of the campaign.[232] He left on March 29 to join Ramírez y Sesma, leaving only a small force to hold Béxar.[233] At dawn on April 7, their combined force marched into San Felipe and captured a Texian soldier, who informed Santa Anna that the Texians planned to retreat further if the Mexican army crossed the Brazos River.[234] Unable to cross the Brazos due to the small company of Texians barricaded at the river crossing, on April 14 a frustrated Santa Anna led a force of about 700 troops to capture the interim Texas government.[235][236] Government officials fled mere hours before Mexican troops arrived in Harrisburg, and Santa Anna sent Colonel Juan Almonte with 50 cavalry to intercept them in New Washington. Almonte arrived just as Burnet shoved off in a rowboat, bound for Galveston Island. Although the boat was still within range of their weapons, Almonte ordered his men to hold their fire so as not to endanger Burnet's family.[237]

At this point, Santa Anna believed the rebellion was in its final death throes. The Texian government had been forced off the mainland, with no way to communicate with its army, which had shown no interest in fighting. He determined to block the Texian army's retreat and put a decisive end to the war.[237] Almonte's scouts incorrectly reported that Houston's army was going to Lynchburg Crossing, on Buffalo Bayou, in preparation for joining the government in Galveston, so Santa Anna ordered Harrisburg burned and pressed on towards Lynchburg.[237]

The Texian army had resumed their march eastward. On April 16, they came to a crossroads; one road led north towards Nacogdoches, the other went to Harrisburg. Without orders from Houston and with no discussion amongst themselves, the troops in the lead took the road to Harrisburg. They arrived on April 18, not long after the Mexican army's departure.[238] That same day, Deaf Smith and Henry Karnes captured a Mexican courier carrying intelligence on the locations and future plans of all of the Mexican troops in Texas. Realizing that Santa Anna had only a small force and was not far away, Houston gave a rousing speech to his men, exhorting them to "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad". His army then raced towards Lynchburg.[239] Out of concern that his men might not differentiate between Mexican soldiers and the Tejanos in Seguín's company, Houston originally ordered Seguín and his men to remain in Harrisburg to guard those who were too ill to travel quickly. After loud protests from Seguín and Antonio Menchaca, the order was rescinded, provided the Tejanos wear a piece of cardboard in their hats to identify them as Texian soldiers.[240]

San Jacinto

[edit]The area along Buffalo Bayou had many thick oak groves, separated by marshes. This type of terrain was familiar to the Texians and quite alien to the Mexican soldiers.[241] Houston's army, comprising 900 men, reached Lynch's Ferry mid-morning on April 20; Santa Anna's 700-man force arrived a few hours later. The Texians made camp in a wooded area along the bank of Buffalo Bayou; while the location provided good cover and helped hide their full strength, it also left the Texians no room for retreat.[242][243] Over the protests of several of his officers, Santa Anna chose to make camp in a vulnerable location, a plain near the San Jacinto River, bordered by woods on one side, marsh and lake on another.[241][244] The two camps were approximately 500 yards (460 m) apart, separated by a grassy area with a slight rise in the middle.[245] Colonel Pedro Delgado later wrote that "the camping ground of His Excellency's selection was in all respects, against military rules. Any youngster would have done better."[246]

Over the next several hours, two brief skirmishes occurred. Texians won the first, forcing a small group of dragoons and the Mexican artillery to withdraw.[241][247] Mexican dragoons then forced the Texian cavalry to withdraw. In the melee, Rusk, on foot to reload his rifle, was almost captured by Mexican soldiers, but was rescued by newly arrived Texian volunteer Mirabeau B. Lamar.[247] Over Houston's objections, many infantrymen rushed onto the field. As the Texian cavalry fell back, Lamar remained behind to rescue another Texian who had been thrown from his horse; Mexican officers "reportedly applauded" his bravery.[248] Houston was irate that the infantry had disobeyed his orders and given Santa Anna a better estimate of their strength; the men were equally upset that Houston had not allowed a full battle.[249]

Throughout the night, Mexican troops worked to fortify their camp, creating breastworks out of everything they could find, including saddles and brush.[250] At 9 a.m. on April 21, Cos arrived with 540 reinforcements, bringing the Mexican force to 1,200 men, which outnumbered the Texians.[251] Cos's men were raw recruits rather than experienced soldiers, and they had marched steadily for more than 24 hours, with no rest and no food.[252] As the morning wore on with no Texian attack, Mexican officers lowered their guard. By afternoon, Santa Anna had given permission for Cos's men to sleep; his own tired troops also took advantage of the time to rest, eat, and bathe.[253]

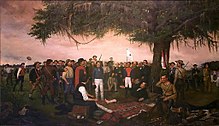

Not long after the Mexican reinforcements arrived, Houston ordered Smith to destroy Vince's Bridge, 5 miles (8.0 km) away, to slow down any further Mexican reinforcements.[254] At 4 p.m. the Texians began creeping quietly through the tall grass, pulling the cannon behind them.[255] The Texian cannon fired at 4:30, beginning the battle of San Jacinto.[256] After a single volley, Texians broke ranks and swarmed over the Mexican breastworks to engage in hand-to-hand combat. Mexican soldiers were taken completely by surprise. Santa Anna, Castrillón, and Almonte yelled often conflicting orders, attempting to organize their men into some form of defense.[257] Within 18 minutes, Mexican soldiers abandoned their campsite and fled for their lives.[258] The killing lasted for hours.[259]

Many Mexican soldiers retreated through the marsh to Peggy Lake.[Note 14] Texian riflemen stationed themselves on the banks and shot at anything that moved. Many Texian officers, including Houston and Rusk, attempted to stop the slaughter, but they were unable to gain control of the men. Texians continued to chant "Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!" while frightened Mexican infantry yelled "Me no Alamo!" and begged for mercy to no avail.[260] In what historian Davis called "one of the most one-sided victories in history",[261] 650 Mexican soldiers were killed and 300 captured.[262] Eleven Texians died, with 30 others, including Houston, wounded.[263]

Although Santa Anna's troops had been thoroughly vanquished, they did not represent the bulk of the Mexican army in Texas. An additional 4,000 troops remained under the commands of Urrea and General Vicente Filisola.[264] Texians had won the battle due to mistakes made by Santa Anna, and Houston was well aware that his troops would have little hope of repeating their victory against Urrea or Filisola.[265] As darkness fell, a large group of prisoners were led into camp. Houston initially mistook the group for Mexican reinforcements and shouted out that all was lost.[266]

Mexican retreat and surrender

[edit]

Santa Anna had successfully escaped towards Vince's Bridge.[267] Finding the bridge destroyed, he hid in the marsh and was captured the following day.[262] He was brought before Houston, who had been shot in the ankle[Note 15] and badly wounded.[264] Texian soldiers gathered around, calling for the Mexican general's immediate execution. Bargaining for his life, Santa Anna suggested that he order the remaining Mexican troops to stay away.[268] In a letter to Filisola, who was now the senior Mexican official in Texas, Santa Anna wrote that "yesterday evening [we] had an unfortunate encounter" and ordered his troops to retreat to Béxar and await further instructions.[265]

Urrea urged Filisola to continue the campaign. He was confident that he could successfully challenge the Texian troops. According to Hardin, "Santa Anna had presented Mexico with one military disaster; Filisola did not wish to risk another."[269] Spring rains ruined the ammunition and rendered the roads almost impassable, with troops sinking to their knees in mud. Mexican troops were soon out of food, and began to fall ill from dysentery and other diseases.[270] Their supply lines had completely broken down, leaving no hope of further reinforcements.[271] Filisola later wrote that "Had the enemy met us under these cruel circumstances, on the only road that was left, no alternative remained but to die or surrender at discretion".[270]

For several weeks after San Jacinto, Santa Anna continued to negotiate with Houston, Rusk, and then Burnet.[272] Santa Anna suggested two treaties, a public version of promises made between the two countries, and a private version that included Santa Anna's personal agreements. The Treaties of Velasco required that all Mexican troops retreat south of the Rio Grande and that all private property – code for slaves – be respected and restored. Prisoners-of-war would be released unharmed, and Santa Anna would be given passage to Veracruz immediately. He secretly promised to persuade the Mexican Congress to acknowledge the Republic of Texas and to recognize the Rio Grande as the border between the two countries.[273]

When Urrea began marching south in mid-May, many families from San Patricio who had supported the Mexican army went with him. When Texian troops arrived in early June, they found only 20 families remaining. The area around San Patricio and Refugio suffered a "noticeable depopulation" in the Republic of Texas years.[274] Although the treaty had specified that Urrea and Filisola would return any slaves their armies had sheltered, Urrea refused to comply. Many former slaves followed the army to Mexico, where they could be free.[275] By late May the Mexican troops had crossed the Nueces.[270] Filisola fully expected that the defeat was temporary and that a second campaign would be launched to retake Texas.[271]

Aftermath

[edit]Military

[edit]When Mexican authorities received word of Santa Anna's defeat at San Jacinto, flags across the country were lowered to half staff and draped in mourning.[276] Denouncing any agreements signed by Santa Anna, a prisoner of war, the Mexican authorities refused to recognize the Republic of Texas.[277] Filisola was derided for leading the retreat and quickly replaced by Urrea. Within months, Urrea gathered 6,000 troops in Matamoros, poised to reconquer Texas. However, the renewed Mexican invasion of Texas never materialized as Urrea's army was redirected to address continued federalist rebellions in other state regions in Mexico.[278]

Most in Texas assumed the Mexican army would return quickly.[279] So many American volunteers flocked to the Texian army in the months after the victory at San Jacinto that the Texian government was unable to maintain an accurate list of enlistments.[280] Out of caution, Béxar remained under martial law throughout 1836. Rusk ordered that all Tejanos in the area between the Guadalupe and Nueces Rivers migrate either to east Texas or to Mexico.[279] Some residents who refused to comply were forcibly removed. New Anglo settlers moved in and used threats and legal maneuvering to take over the land once settled by Tejanos.[277][281] Over the next several years, hundreds of Tejano families resettled in Mexico.[277]

For years, Mexican authorities used the reconquering of Texas as an excuse for implementing new taxes and making the army the budgetary priority of the impoverished nation.[282] Only sporadic skirmishes resulted.[283] Larger expeditions were postponed as military funding was consistently diverted to other rebellions, out of fear that those regions would ally with Texas and further fragment the country.[282][Note 16] The northern Mexican states, the focus of the Matamoros Expedition, briefly launched an independent Republic of the Rio Grande in 1839.[284] The same year, the Mexican Congress considered a law to declare it treasonous to speak positively of Texas.[285] In June 1843, leaders of the two nations declared an armistice.[286]

Republic of Texas

[edit]

On June 1, 1836, Santa Anna boarded a ship to travel back to Mexico. For the next two days, crowds of Texian soldiers, many of whom had arrived that week from the United States, gathered to demand his execution. Lamar, by now promoted to Secretary of War, gave a speech insisting that "Mobs must not intimidate the government. We want no French Revolution in Texas!", but on June 4 soldiers seized Santa Anna and put him under military arrest.[287] According to Lack, "the shock of having its foreign policy overturned by popular rebellion had weakened the interim government irrevocably".[288] A group of soldiers staged an unsuccessful coup in mid-July.[289] In response, Burnet called for elections to ratify the constitution and elect a Congress,[290] the sixth set of leaders for Texas in a 12-month period.[291] Voters overwhelmingly chose Houston the first president, ratified the constitution drawn up by the Convention of 1836, and approved a resolution to request annexation to the United States.[292] Houston issued an executive order sending Santa Anna to Washington, D.C., and from there he was soon sent home.[293]

During his absence, Santa Anna had been deposed. Upon his arrival, the Mexican press wasted no time in attacking him for his cruelty towards those prisoners executed at Goliad. In May 1837, Santa Anna requested an inquiry into the event.[294] The judge determined the inquiry was only for fact-finding and took no action; press attacks in both Mexico and the United States continued.[295] Santa Anna was disgraced until the following year, when he became a hero of the Pastry War.[296]

The first Texas Legislature declined to ratify the treaty Houston had signed with the Cherokee, declaring he had no authority to make any promises.[132] Although the Texian interim governments had vowed to eventually compensate citizens for goods that were impressed during the war efforts, for the most part livestock and horses were not returned.[297] Veterans were guaranteed land bounties; in 1879, surviving Texian veterans who served more than three months from October 1, 1835, through January 1, 1837, were guaranteed an additional 1,280 acres (520 ha) in public lands.[298] Over 1.3 million acres (530 thousand ha) of land were granted; some of this was in Greer County, which was later determined to be part of Oklahoma.[299]

Republic of Texas policies changed the status of many living in the region. The constitution forbade free blacks from living in Texas permanently. Individual slaves could only be freed by congressional order, and the newly emancipated person would then be forced to leave Texas.[300] Women also lost significant legal rights under the new constitution, which substituted English common law practices for the traditional Spanish law system. Under common law, the idea of community property was eliminated, and women no longer had the ability to act for themselves legally – to sign contracts, own property, or sue. Some of these rights were restored in 1845, when Texas added them to the new state constitution.[301] During the Republic of Texas years, Tejanos likewise faced much discrimination.[302]

Foreign relations

[edit]Mexican authorities blamed the loss of Texas on United States intervention.[276] Although the United States remained officially neutral,[303] 40 percent of the men who enlisted in the Texian army from October 1 through April 21 arrived from the United States after hostilities began.[304] More than 200 of the volunteers were members of the United States Army; none were punished when they returned to their posts.[303] American individuals also provided supplies and money to the cause of Texian independence.[305] For the next decade, Mexican politicians frequently denounced the United States for the involvement of its citizens.[306]

The United States agreed to recognize the Republic of Texas in March 1837 but declined to annex the territory.[307] The fledgling republic now attempted to persuade European nations to agree to recognition.[308] In late 1839 France recognized the Republic of Texas after being convinced it would make a fine trading partner.[309]

For several decades, official British policy was to maintain strong ties with Mexico in the hopes that the country could stop the United States from expanding further.[310] When the Texas Revolution erupted, Great Britain had declined to become involved, officially expressing confidence that Mexico could handle its own affairs.[311] In 1840, after years in which the Republic of Texas was neither annexed by the United States nor reabsorbed into Mexico, Britain signed a treaty to recognize the nation and act as a mediator to help Texas gain recognition from Mexico.[312]

The United States voted to annex Texas as the 28th state in March 1845.[313] Two months later, Mexico agreed to recognize the Republic of Texas as long as there was no annexation to the United States.[314] On July 4, 1845, Texians voted for annexation.[315] This prompted the Mexican–American War, in which Mexico lost almost 55 percent of its territory to the United States and formally relinquished its claim on Texas.[316]

Legacy

[edit]

Although no new fighting techniques were introduced during the Texas Revolution,[317] casualty figures were quite unusual for the time. Generally, in 19th-century warfare, the number of wounded outnumbered those killed by a factor of two or three. From October 1835 through April 1836, approximately 1,000 Mexican and 700 Texian soldiers died, while the wounded numbered 500 Mexican and 100 Texian. The deviation from the norm was due to Santa Anna's decision to label Texian rebels as traitors and to the Texian desire for revenge.[318]

During the revolution, Texian soldiers gained a reputation for courage and militance.[302][304] Lack points out that fewer than five percent of the Texian population enrolled in the army during the war, a fairly low rate of participation.[304] Texian soldiers recognized that the Mexican cavalry was far superior to their own. Over the next decade, the Texas Rangers borrowed Mexican cavalry tactics and adopted the Spanish saddle and spurs, the lasso, and the bandana.[319]

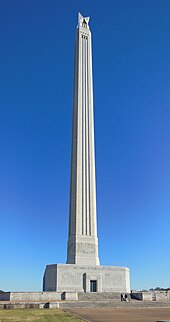

The Texas Veterans Association, composed solely of revolutionary veterans living in Texas, was active from 1873 through 1901 and played a key role in convincing the legislature to create a monument to honor the San Jacinto veterans.[320] In the late 19th century, the Texas Legislature purchased the San Jacinto battlesite, which is now home to the San Jacinto Monument, the tallest stone column monument in the world.[321] In the early 20th century, the Texas Legislature purchased the Alamo Mission,[322] now an official state shrine.[323] In front of the church, in the center of Alamo Plaza, stands a cenotaph designed by Pompeo Coppini which commemorates the defenders who died during the battle.[324] More than 2.5 million people visit the Alamo every year.[325]

The Texas Revolution has been the subject of poetry and of many books, plays and films. Most English-language treatments reflect the perspectives of the Anglos and are centered primarily on the battle of the Alamo.[326] From the first novel depicting events of the revolution, 1838's Mexico versus Texas, through the mid-20th century, most works contained themes of anticlericalism and racism, depicting the battle as a fight for freedom between good (Anglo Texian) and evil (Mexican).[327] In both English- and Spanish-language literature, the Alamo is often compared to the battle of Thermopylae.[328] The 1950s Disney miniseries Davy Crockett, which took considerable license with its source material, inspired worldwide interest in the battle.[329] Within several years, John Wayne directed and starred in one of the best-known and perhaps least historically accurate film versions, The Alamo (1960).[330][Note 17] Notably, this version made the first attempt to leave behind racial stereotypes; it was still banned in Mexico.[331] In the late 1970s, works about the Alamo began to explore Tejano perspectives, which had been all but extinguished even from textbooks about the revolution, and to explore the revolution's links to slavery.[332]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Spain did not ratify the treaty until February 1821, in the hopes that the delay would stop the Americans from recognizing Mexico as an independent country. Weber (1992), p. 300.

- ^ For the purposes of this article, "Texas" refers to the area north of the Medina and Nueces Rivers and west of the Sabine River. "Coahuila y Tejas" comprises both Texas and the province of Coahuila. The "Republic of Texas" includes Texas and the land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande.

- ^ David Weber (1992), p. 166, states that in 1830, there were approximately 7,000 foreign-born residents and 3,000 Mexican-born residents. Todish et al. (1998), p. 4, states that there were 16,000 Anglos and only 4,000 Mexican-born residents in Texas in 1830.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 26. claims 14 Mexican soldiers died. Todish et al. (1998), p. 23. estimated 60 Mexican casualties. Hardin (1994), p. 34. claims 76 Mexican soldiers died.

- ^ Milam was killed by a sharpshooter on December 7. Edmondson (2000), p. 243.

- ^ If those who arrived after the battle of Gonzales are included, the average immigration date is 1832. Lack (1992), pp. 114–115.

- ^ These numbers are gathered from a combination of surviving muster rolls and veteran applications for land grants. It is likely that the statistics on the Texian army size in both 1835 and 1836 underestimate the number of Tejanos who served in the army. American volunteers who returned to the U.S. without claiming land are also undercounted. Lack (1992), p. 113.

- ^ As of March 2015, no other historian has examined Reid's theory in detail. The Texas State Historical Association's article on Grant was written by Reid and includes mention of this theory.

- ^ Houston's orders to Bowie were vague, and historians disagree on their intent. An alternative interpretation is that Bowie's orders were to destroy only the barricades that the Mexican army had erected around San Antonio de Béxar, and that he should then wait in the Alamo until Governor Henry Smith decided whether the mission should be demolished and the artillery removed. Smith never gave orders on this issue. Edmondson (2000), p. 252.

- ^ The Sabine River marked the eastern border of Mexican Texas.

- ^ Brigido Guerrero convinced the Mexican army he had been imprisoned by the Texians. Joe, the slave of Alamo commander William B. Travis, was spared because he was a slave. Some historians also believe that Henry Warnell hid during the battle, although he may have been a courier who left before the battle began. He died several months after the battle of wounds incurred during his escape. See Edmondson (2000), pp. 372, 407.

- ^ Groce's Landing is located roughly 9 miles (14 km) northeast of modern-day Bellville. Moore (2004), p. 149.

- ^ After getting inaccurate reports that several thousand Indians had joined the Mexican army to attack Nacogdoches, American General Edmund P. Gaines and 600 troops crossed into Texas. This would have provoked a war if they had encountered the Mexican army, which might have followed Houston if he continued his retreat. Reid (2007), pp. 152–153.

- ^ Peggy Lake, also called Peggy's Lake, no longer exists. It was located southeast of the Mexican breastworks, which is now the site of the monument. Hardin (2004) pp. 71, 93

- ^ Lamar thought Houston was deliberately shot by one of his own men. Moore (2004), p. 339.

- ^ New Mexico, Sonora, and California revolted unsuccessfully; their stated goals were a change in government, not independence. Henderson (2008), p. 100. Vazquez (1985), p. 318.

- ^ Historians J. Frank Dobie and Lon Tinkle requested that they not be listed as historical advisers in the credits of The Alamo because of its disjunction from recognized history. Todish et al. (1998), p. 188.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Torget 2015, p. 140.

- ^ Carrigan 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Kelley 2004, p. 716.

- ^ Campbell 1991, p. 256.

- ^ Lack 1985, p. 190.

- ^ Weber (1992), pp. 149–154.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 6.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 10.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 291.

- ^ Thonhoff, Robert H. (1952). "Medina, Battle of". Handbook of Texas. TSHA. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Weber (1992), pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b Lack 1992, p. 5.

- ^ Manchaca (2001), pp. 161–162.

- ^ Vazquez (1997), p. 51.

- ^ a b Davis (2006), p. 63.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 72.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 75.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 162.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 161.

- ^ Weber (1992), p. 166.

- ^ Manchaca (2001), p. 164.

- ^ Davis (2006), pp. 60, 64.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 80.

- ^ Manchaca (2001), p. 200.

- ^ Manchaca (2001), p. 201.

- ^ Manchaca (2001), p. 172.

- ^ Baptist (2014), p. 266.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 78.

- ^ Winders (2004), p. 20.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 89.

- ^ Davis (2006), pp. 92, 95.

- ^ Davis (2006), pp. 110, 117.

- ^ Vazquez (1997), p. 69.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 117.

- ^ Vazquez (1997), p. 67.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 120.

- ^ a b Davis (2006), p. 121.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 6.

- ^ a b c Hardin (1994), p. 7.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 122.

- ^ Lack 1992, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 23.

- ^ Lack 1992, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 131.

- ^ Lack 1992, p. 25.

- ^ Lack 1992, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Lack 1992, p. 20.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 198.

- ^ a b Davis (2006), p. 199.

- ^ Davis (2006), pp. 136, 138.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 133.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 74.

- ^ a b c Winders (2004), p. 54.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 138.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 137.

- ^ Davis (2006), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 12.

- ^ a b Davis (2006), p. 142.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 13.

- ^ a b Winders (2004), p. 55.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 26.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 14.

- ^ Hardin (1994), pp. 15–17.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 148.

- ^ Lack (1992), p. 190.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 42.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 44.

- ^ a b Davis (2006), p. 176.

- ^ Lack (1992), p. 157.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 46.

- ^ Hardin (1994), pp. 17, 19.

- ^ Lack (1992), pp. 190–191.

- ^ Lack (1992), pp. 162–163.

- ^ Lack (1992), p. 162.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 6.

- ^ Lack (1992), p. 41.

- ^ Davis (2006), pp. 150–151.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 151.

- ^ a b Davis (2006), p. 152.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 19.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 22.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 23.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 26.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 33.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 60.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 35.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 29.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 35.